Fiddle & Pint

Exhibition of New Works in Mixed Media

by Gertrude Degenhardt

24th September - 14th October 1999

Comments made by Bob Quinn at the Opening of Fiddle & Pint

Last year I guest edited the Sligo magazine, Force10, and asked Martin Degenhardt would his wife Gertrude provide a picture for it. They sent me an etching of a demure young lady, eyes closed, long skirt modestly down to her toes, playing the fiddle. The title was "How elegance came into Irish music". I could hear the Cúilfhionn being played with all the sickly passion of a genteel turn of the century drawing room, the Thomas Moore sentimentality, scooping notes, all the impersonations that made traditional Irish music a turnoff and have since made it sexy - although now the girl would be gyrating in a pussy pelment.

Last year I guest edited the Sligo magazine, Force10, and asked Martin Degenhardt would his wife Gertrude provide a picture for it. They sent me an etching of a demure young lady, eyes closed, long skirt modestly down to her toes, playing the fiddle. The title was "How elegance came into Irish music". I could hear the Cúilfhionn being played with all the sickly passion of a genteel turn of the century drawing room, the Thomas Moore sentimentality, scooping notes, all the impersonations that made traditional Irish music a turnoff and have since made it sexy - although now the girl would be gyrating in a pussy pelment.

It reminded me what an acute and mercilessly funny observer Gertrude Degenhardt is - not only of this, her adopted home, but also of human beings in general. Because make no mistake, this woman is not just talking about Spiddal and Galway, she is talking about the human race, exposing us to our own absurdity and reminding us of one of our few redeeming features; music.

I use the word "talking" on purpose because Degenhardt's pictures speak volumes, to me at least. I see stories in them, epiphanies, and snatches of conversations, tragedies, jokes, nonsense rhymes, dirty Limericks - and poetry. And after a session of looking at them I am left silent, wondering how any stranger could have got into our psyches and exposed them so perceptively. Then, I realise she is not being personal- simply showing what it is to be human.

I imagine her years ago sitting like a mouse in the corner of a pub, antennae vibrating, eyes absorbing everything, the only noise her needle scratching on copper or her pencil dancing over the paper. But I also imagine the noises that touched her: the silence of the afternoon pub, the sighs of solitary drinkers, the wind when the door let in company, then the rising tide of drinkers, garrulous conversations, curses, screeching fiddles, imprecations, threats, quartets, quintets, twenty-tets sometimes, tin whistles, out of tune guitars, brass intrusions, melodeons, roaring arguments, gusts of laughter, yelps of dogs, hawking coughs, the splat of spits, indignant bar stools, the silence at the start of a solo, the growing murmur, then the drowning out of the music. Above all, laughter. Then the wind above in Shanagurraun.

I came to Conamara about the same time as Gertrude. It must have been as much a shock to her as it was to me. For years I have looked at her pictures in disbelief. How could she show what I thought only I could see? No Paul Henry nonsense. She saw the people, teems of them, vibrant, alive, loud, unreserved, talking twenty to the dozen, drinking, dancing, singing, arguing, fighting, with an urgency and vitality that neither I nor she had experienced before, except in the performance of music. These people were not desiccated. They lived operatically. And you're right: I see and hear what I want to see. Conamara is what I see and hear in her pictures. To me they are cunningly devised Rohrshach inkblots, amenable to the wildest speculation. All good pictures are.

But Degenhardt is also a documentarist. What I see in her work is a chronicling of the sea changes of the past twenty years. For want of a better description I call it the Feminisation of the Irish Pub. In her "Farewell to Connaught" cycle long age this was an all male world - apart from the Mother Earth presence of such as Breda Hughes and Mary Bergin.

Men could behave badly, trusting each other not to tell. They could drink thirteen pints, spilling, a few more, balance them on their heads, weep into them, share them with rodents and predatory seagulls, tell their life stories to complete strangers, tell more to nobody in particular, invoke God and then take his name in vain, imagine they were birds, lead imaginary charges on invincible enemies and, just in case, carry a white flag, alternately swear undying loyalty and hatred to each other, utter terrible curses at the worlds, then say "sin an saol"( that's life), and biodh an fheamuinn acub" (let them have their way ) demonstrate impossible tricks with chairs, have another drink. And another. And another. Defy the force of gravity. Dance like the fairies. Sing like crows. Threaten with shushes. Without the slightest trace of self-consciousness. And laugh like demons. And no women around to tut - tut or give them "that look" or drag them home protesting. It was a male paradise- except for the cold stumble home in the rain.

And Degenhardt heard the notes of desperation in their laughter. And for a while she averted her eyes. She was at her most explicit about this in her " Vagabondage Ad Mortem" cycle. Her skeletons played and danced as if there was no tomorrow. And there wasn't. Where could she go?

Women began to take over her pictures ( Vagabondage in Blue" cycle), wild women on the warpath banging drums- bin lids? Women celebrating, behaving defiantly, in contortions, in quartets, in impossible postures. Then she took pity on men and brought the sexes together in quartets. She went Baroque. But this was a woman's world of music. There were new rules. The men must occasionally listen, eat the odd meal, and put on a bit of weight, dress a little more carefully.

Then she returned to Hughes's pub. She was still seeing the same things but she introduced the Séimhiú into Irish pub life. Séimhiú (pronounced 'chez vous'!) means, "a softening". Men must no longer go on mad scarecrow solo runs. Unless they were Mick Mulcahy the painter whom I saw in tights doing an impersonation of Nijinsky - the dancer - one evening in Hughes. Finally Degenhardt has decided that women and men may co-exist. This exhibition is the wedding feast.

The cold desperation of "Farewell to Connaught" is a memory. The harshness of those unforgettable dry point etchings has been replaced by tender, subtle brush strokes. This is the Séimhiú. Life is softer here and Gertrude has become kinder. There is desperation still, hysteria too, abandon even - who wouldn't be intimidated by Millie the Tit - but the sexes are no longer miles apart. Music brings them together. They prop each other up, drunk and sober. That's as it should be. They still play with themselves, of course. But they play with the women too. And the women play with them: duets, quartets, whatever you're having yourself. Men are still in the majority, of course, but there are changes.

I notice something else about these new men. They engage in the same gravity-defying callisthenics but there is a self-consciousness about them that wasn't there ten, twenty years ago. They almost seem to be performing, aware of the audience, performing cartwheels for the girls - maybe even for the tourists. Sometimes they are balletic. There is a different kind of desperation- a quieter kind. It may be grace under fire. It may be "biseach an bás" - the last hopeful gasp. Either they have changed or Gertrude has. Perhaps both. I suspect she has become closer to them now, understands their different kind of desperation. She noted the effect of "elegance" on them. Or maybe I'm reading too much into brush strokes. Whatever it is - good or ill she has pinned it down. She is a visual anthropologist. Fair play to her.

One thing I haven't referred to and that is the Degenhardt genius. Do I have to? Look around these walls. Si monumentum require circumspice. We're lucky that the Degenhardts adopted Galway as their second home. We're lucky that Tom Kenny adopted them. Some day I hope to see a colour etching of Tom and Martin talking about drinking. I warn them both: Gertrude is watching.

And before I say anything indiscreet I declare to God! This exhibition is now officially open.

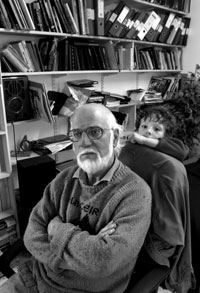

Bob Quinn